It’s been more than a month since a 9.0 magnitude earthquake rocked Japan, triggering a massive tsunami, the combination of which have killed thousands. And while the country is slowing putting itself together, under the looming dangers of a potential nuclear disaster, there are many organizations — and individuals — coming together to help in any way they can.

For this week’s post, I chatted with Our Man in Abiko, an international man of mystery behind #Quakebook, a crowdsourced project to help those affected by the devastation.

NOTE: The Q&A was done through e-mail over a course of a couple of weeks.

First, for those who don’t know about it, can you describe what the #Quakebook is, how it came about and your role?

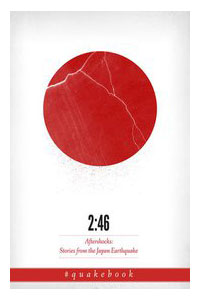

Quakebook is a Twitter-sourced anthology of first-person accounts of the earthquake and immediate aftermath. It was conceived, written and ready to publish as a fully designed PDF book within a week. It has 89 contributions from “real” people as well as 4 from celebs solicited thru Twitter – William Gibson, Yoko Ono, Barry Eisler and Jake Adelstein.

Quakebook is a Twitter-sourced anthology of first-person accounts of the earthquake and immediate aftermath. It was conceived, written and ready to publish as a fully designed PDF book within a week. It has 89 contributions from “real” people as well as 4 from celebs solicited thru Twitter – William Gibson, Yoko Ono, Barry Eisler and Jake Adelstein.

It is not a collection of tweets, but mostly one-page essays.

I thought of it in the shower Friday morning, March 18th thinking that wouldn’t it be great to do in words what mash-up videos can do on YouTube, especially @fatblueman’s Christmas in Japan video. Check it out, you’ll see what I mean. [The video: http://youtu.be/lmCrIZeob4w]

No-one has received a penny. We got Amazon to waive their fees so ALL revenue goes to the Red Cross. Pinch me, I’m dreaming.

Oh, my role? I’m cheerleader in chief, marshaller of the troops and getter-arounder of problems. Don’t like titles!

NOTE: Our Man recently did a video recently sharing the story of Quakebook: http://youtu.be/cQ_-3-wwLKs

Once you had this idea, how did you go about starting this? Can you talk about the crowdsourcing process?

I had no plan as such. Every time I hit a wall, I asked the good folk of Twitter to give me a leg up 🙂

The original tweets and stuff are all on quakebook.org and www.ourmaninabiko.com

Talk about the “real” people that contributed to the collection. Have you ever met them? What journalism skills did you apply in collecting their stories?

The real people started with whoever sent me email from around the world, supplemented by my neighbours, my wife and mother-in-law, and also I got my wife to chase down eyewitness accounts from devastated areas through blogs.

The celebs we picked up along the way. The highly unscientific approach has somehow created a snapshot of many disparate elements of the disaster.

I kept in anything that was sent and was not a rant or shopping list. (There were only two like this).

What is your ideal goal you hope to achieve with this book?

I want it to raise oodles and noodles of cash for the Red Cross, but beyond that, I want it to serve as a valuable historical record to answer the question: What happened at 2:46 on March 11, much like John Hersey’s “Hiroshima” answers What happened on Aug. 6, 1945.

What has been the best part of this project?

The therapy of writing and sharing what we have written; seeing the whole project becoming stronger than its constituent parts.

What has surprised you about the process? What’s been the highlight?

How the weekend stops dead any progress with the traditional publishing industry, while the reverse is true of us amateurs. The highlight? Seeing a tweet from someone that they had downloaded the book, and cried. I then did the same and got teary eyed too.

What do you think about those reluctant to use crowdsourcing in storytelling, particularly in journalism. Any advice to them?

Trust people to deliver, and they will. If you get sidetracked by someone with their own agenda, or who doesn’t get the point of the project, don’t waste your time, find someone who does. Behave morally and you will quickly attract the right kind to whatever your project is, if it has merit.

Can you tell me what you did prior to this project? What were you doing in Japan? Talk about Our Man In Abiko.

I’m a British self-employed English language teacher, 40. I’m a former local newspaper journalist. My wife is Japanese and we’ve been here since 2007. Got two kids. My favourite colour is red.

Our Man in Abiko began as a satirical blog on Japanese politics, and became a persona to keep me sane.

Since the earthquake, I realised Our Man was needed to perform Churchillian tasks of rallying the dispirited to overcome our woes.

What is the backstory with Our Man in Abiko? What’s your name and what brought you to Japan?

Not saying. It’s not my story that’s interesting, it’s Japan’s.

Clearly the book is the focus, but “Our Man In Abiko” is a man of mystery. People are naturally going to ask, “who is this guy?” What can you tell them?

He likes Earl Grey tea, playing with his kids and world domination, you know, the usual.

[After more prodding]

OK, well, the Our Man persona began just as a joke on my blog, I took on the mantle of a redundant British agent sent to monitor the wilds of Tokyo commuterville… But then with the earthquake, suddenly the time for fun was long gone, but I realised I had a fictional character who could do great things. I could not muster the troops and build a resistance movement to the earthquake, but maybe Our Man in Abiko could.

Well, Our Man, congratulations on the success with this project. How and where can people find it?

All details are on http://www.quakebook.org and you can buy the book now here: http://amzn.to/quakebook for Kindle (you can download a free Kindle player for PC, Mac and Smart phones there too.)

Thanks for chatting with me. And good luck on this and other endeavors.

Thanks a lot.

Robert Hernandez is a Web Journalism professor at USC Annenberg and co-creator of #wjchat, a weekly chat for Web Journalists held on Twitter. You can contact him by e-mail ([email protected]) or through Twitter (@webjournalist). Yes, he’s a tech/journo geek.